July 2025

This month we are looking at some extracts from DDHS member Liz Curtis’ fascinating online book on East Lothian place-names. All text and photos by Liz Curtis and links by Dr James Herring.

Barns Ness

Barness 1752–55

From Scots ness ‘headland’ with the settlement name Barns, from nearby East Barns. Barns Ness is about two miles east of Dunbar, marked by a fine lighthouse built by the Stevensons which is no longer operational. East Barns no longer exists, unlike its twin, West Barns, which is a flourishing village west of Dunbar. East Barns’ misfortune was to be sited on limestone, quarried for multiple uses.

The two parcels of arable land named Barns date back to medieval times, when they belonged to the earldom of Dunbar. In 1435 they became Crown lands when the earl forfeited his estates. The ‘barns’ in question were storage facilities where the tenants deposited their rents, paid in kind. The rents from West and East Barns supplied the garrison at Dunbar Castle.

Over time the tenants gained control of their lands. East Barns became a large farm and associated settlement. The inhabitants departed after the land was sold in 1960 to the cement company known as Blue Circle, which built a cement works and opened limestone quarries. The settlement was quarried away.

The word barns is a common place-name element in lowland Scotland, and indeed in East Lothian in the mid-19th century there were seven farms whose name included the word Barns, or in one case Barney.

Barns Ness NT723772. Dunbar parish.

East Barns NT717762. Dunbar parish.

Barns Ness lighthouse

Bay’s Well

Sanct-Bais-wall 1603

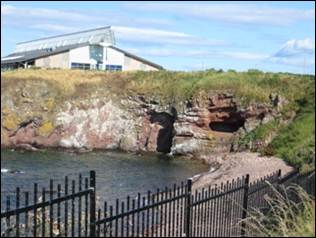

A holy well dedicated to St Bay, in the cliff below Dunbar’s swimming pool. It was described by the Ordnance Survey Name Book as ‘a spring of the purest water’. It has a rock-cut basin to catch the water. The cave should only be entered with great care as it is slippery and gets cut off by the tide. The well gave its name to Bayswell Park, a row of villas built in the 1880s, and to Bayswell Road, which was previously called Westgate End.

St Bay, also spelt Bae or Baye, was the patron saint of Dunbar’s Collegiate Church, founded in 1342 by Patrick V, earl of March, as part of the parish church. Who was St Bay? There are two saints with similar names, who may have been the same person. St Begha, whose feast day is 31 October, was said to have fled from Vikings in Ireland to St Bees in Cumbria. Here a church was dedicated to her, followed by a wealthy priory. It seems likely that the earls of Dunbar, who had close links with Cumbria, brought her cult to Dunbar. There is also St Baya, whose feast day is 3 November, who had a chapel dedicated to her on Little Cumbrae, an island off Scotland’s west coast. The Aberdeen Breviary, published in 1510, identified Baya as the Dunbar saint and explained why her relics had remained on Little Cumbrae:

‘Now just as she led a solitary life in that island while she was living, so also in death she does not allow her body to be taken away from it. For when a parson of the parish church of Dunbar, which is dedicated in her honour… wished to translate the holy virgin’s relics there, he got ships ready and came to the island with a favourable wind; but when he put her bones in a wooden coffin in his ship, such a storm of wind and sea repeatedly arose that they would have been drowned; but as soon as they laid down her remains, they returned again on their desired course.’

NT677791. Dunbar parish.

Site of St Bay’s well (centre)

Dunbar

dyunbaer, dynbaer, 8th cent., copied 11th or early 12th cent.

‘Fort on the point or headland’, from Brittonic dūn or dīn ‘fort’ and barr ‘point, top’. The first record of Dunbar is in The Life of Bishop Wilfrid, a text written in Latin soon after Wilfrid’s death in 709, though the two surviving copies are later. The author describes how Wilfrid was imprisoned by the Northumbrian king Ecgfrith in his urbs or royal centre of Dunbar.

The name Dunbar refers to a fort built by Britons some 2,000 years ago on the headland where the swimming pool now stands. Excavations prior to the building of the pool revealed that ditches were dug across the headland to create a promontory fort. This encompassed the stack where the medieval blockhouse now sits: the ditch between them was cut when the blockhouse was constructed. The Northumbrian stronghold was on the same site. Later excavations on Dunbar High Street uncovered the grave of an Iron Age warrior, equipped with an iron spearhead and an iron sword.

Site of Dunbar’s Iron Age fort

The spellings dyunbaer and dynbaer in the two manuscripts could both imply an 8th-century pronunciation with a vowel similar to Scots muin (‘moon’), or perhaps French tu. Gaelic-speaking Scots, arriving in the area from the 10th century onwards, would have understood the name and pronounced it similarly. The stress in both languages would have been on the second syllable.

The 16th-century historian Hector Boece (pronounced Boyce), who is not famed for his accuracy, interpreted the name as Gaelic and spun a highly coloured tale from it, flattering the monarchy and aristocracy. Writing in Latin, later translated into Scots by John Bellenden and English by Raphael Holinshed, Boece described how a valiant warrior called Bar played a prominent role in Kenneth mac Alpin’s mythical victory over the Picts, and was rewarded with the strongest castle in the land. He wrote that Kenneth inflicted genocidal slaughter on the Picts, then seized their lands, dividing them among his nobles. Holinshed translates: ‘He added newe names also unto every quarter and region… that the memory of the Pictishe names might ende togither with the inhabitants.’ Then: ‘The strongest castle of the whole countrey Kenneth bestowed upon that valiant Captaine named Bar… That fortresse ever sithence (after his name) hath bene called Dunbar, that is to say, the Castell of Bar.’ Boece then praised the ‘noble house’ of Dunbar, descended from Bar, who included the Earls of March.

Hector Boece (1465?–1536)

Contemporary portrait, artist unknown

Wikimedia Commons

The story surfaced in the work of Boece’s translators and in George Buchanan’s History of Scotland (1582). A challenge came in the early 1800s when the historian George Chalmers noted that ‘the town obtained its designation, from the fortlet on the rock, which, at this place, projects into the sea.’ He explained, ‘Dun-bar, in the British, and Dun-bar, in the Gaelic, signify the fort, on the height, top, or extremity’. But Bar was not dead – he reappeared in James Miller’s influential History of Dunbar, published in 1830: Miller retold Boece’s version, while adding Chalmers’ observations as a footnote.

NT679789. Dunbar parish.

Spire of Dunbar Town House

You must be logged in to post a comment.