SEPTEMBER 2022

This month, we are going back to 1898 when Dunbar railway station was the scene of a horrendous crash. Jim Herring has searched The Scotsman archives online and found detailed reports of the crash and its aftermath.

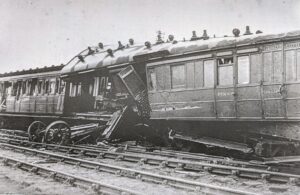

The photo above – in DDHS archives after a lantern slide was digitised by Pauline Smeed – shows the extent of the wreckage after the crash, which involved an express train hitting a standing goods train in the station. On 04 January 1898, the Scotsman headline was “WRECK OF THE SCOTTISH EXPRESS AT DUNBAR: ONE LADY KILLED – SEVERAL PASSENGERS INJURED”. The article began “A terrible disaster occurred to the East Coast Express from London to Edinburgh just outside Dunbar railway station early yesterday morning. The train was badly wrecked and it is a wonder that no more passengers were killed. Unfortunately, one lady met with her death, and five persons were rather seriously injured, while many more sustained minor bruises. Such a catastrophe is likely to throw a gloom over the New Year festivities”. (It would appear that, in 1898, the New Year festivities were still ongoing on 4th January!). The article continued, stating that the express left Kings Cross at 11.30pm sharp and made its way, via Peterborough, to Berwick Upon Tweed where there was a ticket collection. In a social comment on the journey, the article noted that, “due to the courtesy of the conductors” at Berwick, few of the passengers “who were dozing or asleep in the carriages, had been roused at the Border town”.

At Berwick, “the train was taken over by North British officials and two North British engines were attached to it”. This was a time when there were different railway companies in the UK and the North British Railway Company owned the line from Berwick to Edinburgh. The report continues “The train proceeded on its way and just outside of Dunbar disaster, swift and sudden and deplorable, overtook it”.

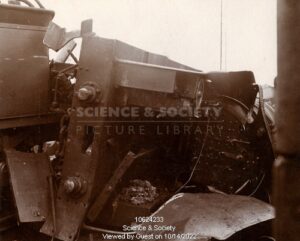

The photo above (best enlarged), also from the DDHS archives, shows more of the wreckage. The Scotsman reported that a waggon from a “mineral train got off the rails” and before the waggon could be removed, “the engines of the express dashed into the waggon on the cross-over and knocked it to pieces, and with the shock upset some waggons on both sides of the railway, which fell inwards towards the ill-fated passenger train”. The train continued for another twenty or thirty yards, taking the waggon with it, “when the leading engine was violently overturned, the bogey going to one side and the body of the locomotive to the other, while the second engine, while it kept its wheels, was also considerably damaged”. The photo shows the “bogie” partially separated from the engine. You can find out more about bogies via this video. In the enlarged version, if you zoom in, you can see written on the door “First” but also above, the words “via The Tay Bridge”. Rail expert Tom Thorburn told Jim Herring “This photo of the derailed train, the coach in question will in my opinion be an East Coast Joint Stock (ECJS)… The ‘Destination Board’ on the coach in question, again in my opinion will be an Aberdeen Express and what you are seeing on the bottom line will be ‘ Via Tay Bridge’. The North British Railway company would be keen to promote the fact that their train was travelling via the Tay Bridge as it was a shorter distance than that of their competitors’ train running via Carlisle, Perth, Stanley Junction, Forfar, Kinnaber Junction to Aberdeen… The ‘Great Races to the North’ highlight the level of competition to get to Aberdeen. In summary, scary speeds and in general whoever got to Kinnaber Junction first had won the race”. You can read more about Kinnaber Junction (good photos) and its history here.

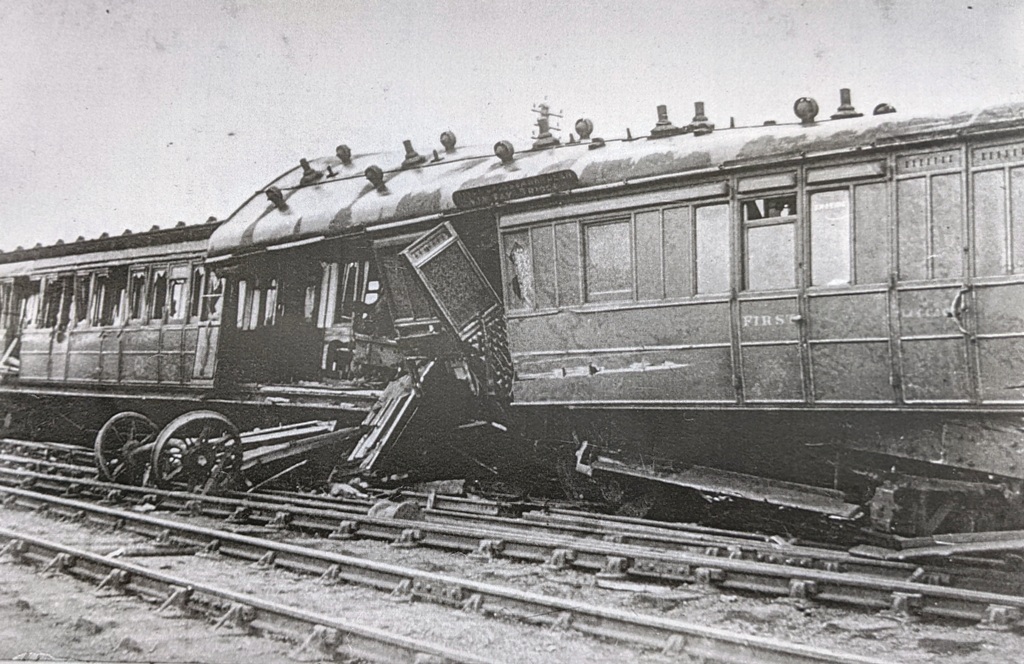

The two photos above (downloaded from the Science and Society Picture Library for non-commercial use) are further evidence of the extent of the wreckage, in that the twisted iron and steel is barely recognisable as part of a railway engine. On 5th January 1898, the Scotsman commented “It was very interesting to observe the effects of the collision on the carriages. The woodwork in many instances was reduced to matchwork, while the ironwork had been wrenched off and twisted in the most remarkable manner, and the axles of the wheels had been torn off and the wheels twisted and otherwise damaged”. One of the injured, Miss Lizzie McAlpine, travelling with her sister Isabella, who was killed in the accident, was in a carriage which was “telescoped fully thirteen feet into the corridor carriage behind”. The surviving Miss McAlpine was reported to “have been staying with Mrs Collingridge at Edenholm” which later became The Eden Hotel. In a further article, The Scotsman reported on the trial of Robert Steedman, the driver of the passenger train, who was accused of entering ” a part of the railway near Dunbar Station while the signals protecting the same were indicating danger, and did cause a collision and did kill Miss Isabella McAlpine, schoolmistress of 5 Clapton Square, London, a passenger on the train”. The driver was found not guilty as it was clear that there was a fault in one of the signals at Dunbar and another was “dimly lit”, so he could not be accused of negligence.

On the 23rd March 1898, The Scotsman reported on the Board of Trade inquiry into the accident. The inquiry found that one of the signalmen in Dunbar was partly at fault for leaving the goods train on the track when the passenger train approached, although the signalman indicated that the signals were at danger. It also faulted the driver who had failed to obey a danger signal. The clear recommendation of the inquiry was that Dunbar station need to ensure that all signals could be clearly seen in future and that the lamps in the signals be “cleaned and trimmed” every other day. The inquiry also recommended that the “distant” signals be moved further away from the “home” signals to allow speeding trains to slow down.

You must be logged in to post a comment.