This month features a new exhibition in Dunbar Town House. The exhibition is very well worth visiting – and telling others about.

The photo above is the poster for the exhibition. In the enlarged photo, you can see that it is very well constructed and eye-catching. The exhibition has been put on by East Lothian Council Museums Service and the photos are here with their permission. Pauline Smeed sourced the images and wrote the text for the wall posters while still working for ELMS. Additional information by Jim Herring

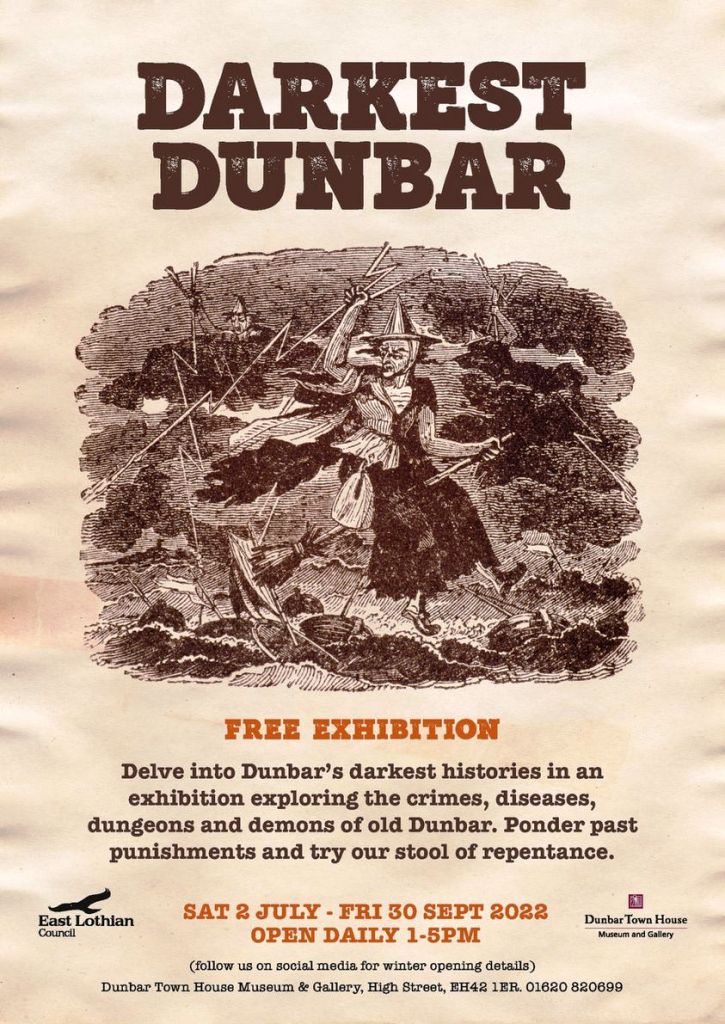

The photo above (please enlarge) tells of the effects of the Black Death and includes the painting by Pierart dou Tielt and you can see a larger version of this here. While the recent Covid pandemic was nothing like this plague, nevertheless you can see some parallels e.g. “quarantine regulations” and particularly “contene themselffs at their awain houssis” was the equivalent of lockdown in the 14th century. It is hard to imagine the grief and suffering amongst the people when one-third of the population died. There were no vaccines then.

Reading the next poster above (please enlarge), you can see that the Act of Parliament of James VI in 1563 was a catch-all for those who might be accused of witchcraft. People are warned that not only must they not use “Witchcraftis Sorcarie or Necromancy” but that they should not learn these “crafts” or, and here is the real catch-all, have “knowledge thairof”. So someone who merely knew about e.g. necromancy i.e. contacting the dead, could be accused. This site tells us that “People believed that the Devil left a mark on his followers when they made a pact with him. So-called ‘witch prickers’ were brought in to prick the accused person with needles numerous times and in intimate places in search of this mark”. Thus women who were seen as strange- or even too lively – could be open to such abuse.

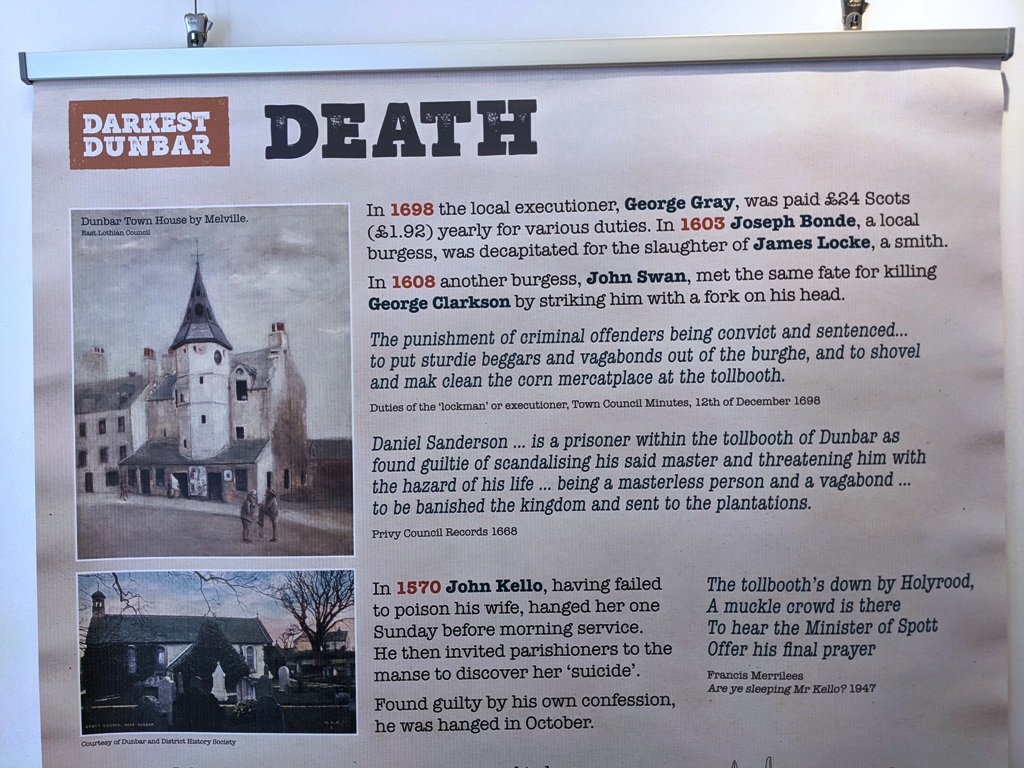

It may seem strange to us now but in the late 17th century, each town of any size would have its own “lockman” or executioner. You can read more about Edinburgh “lokmen” here. The Edinburgh executioner had to be “present to swing the axe, tighten the noose or light the tinder (depending on whether your fate was to be beheaded, hung or burned at the stake)”. We also have to remember that these were public executions and these could be social events which drew large crowds. The Dunbar executioner was also paid for wider duties as indicated by the Town Council in 1698 i.e. to get rid of “sturdie beggars” and to clean up after horses at the toolbooth. You can read a detailed account relating to John Kello, Spott Minister, based on his confession, here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.